IP Two Minute Monthly – April 2020

This is our summary of developments and cases in the world of IP from April which should take no longer than two minutes to read:

02.07.2020

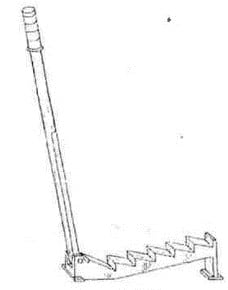

Shapes and trade marks

When considering whether a sign consists exclusively of the shape of the product, the CJEU has ruled that the assessment does not need to be confined to just the graphical representation of the sign. The case related to an application to register the 3D sign shown above. The perception of the public can also be taken into account, but only to identify the essential characteristics of the sign (and not on whether the characteristics of shape perform a technical function). On the issue of whether the shape gives substantial value to the product, if a consumer decides to buy the product based largely on an essential characteristic of its shape, then evidence of that can be taken into account if it is objective and reliable. For decorative items, the exclusion will not automatically apply just because the aesthetic appearance of the product gives it some value. The Court also confirmed that different IP rights can co-exist in the same subject matter, and the fact that different criteria apply to different rights means that you cannot systematically rule out trade mark protection just because, for example, a design is protected by a design right (Gömböc Case C-237/19).

Communication to the public and copyright

The CJEU has ruled that hiring out cars equipped with radio receivers does not constitute a communication to the public. There was no “act of communication” of a work by vehicle rental companies who made the cars available because the Copyright Directive makes it clear that “the mere provision of physical facilities for enabling or making a communication does not in itself amount to communication”. Furthermore, there was no intentional broadcast of protected works by distributing a signal through the radio receivers (Stim and SAMI (C-753/18)).

Individual character and community designs

In rejecting an appeal against a declaration that a registered Community design for a wood-splitting tool was invalid due to lack of individual character, the General Court held that the Board of Appeal had been entitled to take account of the earlier tool in the closed position, even though the representations only showed it open – the closed position could be deduced from the drawing showing the open position. The court also rejected the argument that users familiar with wood-splitting tools would pay little attention to the elements which are commonly found in such tools, such as the teeth, as the teeth could have different shapes, and those elements were also the most visible and important in the designs (Case T-73/19).

Bad faith and trade marks

Following the CJEU’s judgment in the SkyKick case the UK Court pared down Sky’s trade mark registrations on the basis that parts of the specifications were filed in bad faith because they were filed “pursuant to a deliberate strategy of seeking very broad protection of the trade marks regardless of whether it was commercially justified” and “with the intention of obtaining an exclusive right for purposes other than those falling within the functions of a trade mark, namely as a legal weapon against third parties”. However, this decision does not mean that broad specifications will always be inappropriate.

Use in Course of Trade and Trade Marks

When considering whether a trade mark has been used “in the course of trade” (which is required for infringement) the CJEU held that anyone carrying out transactions, by reason of their volume, their frequency or other characteristics, which go beyond the scope of a private activity, will be acting in the course of trade (Case C772/18).

Economic Links, Likelihood of Confusion and Trade Marks

The CJEU has upheld a judgment that a figurative EUTM containing the word “Gugler” was not invalid due to a likelihood of confusion with the company name Gugler France SA. When the EUTM was filed in 2003, there was an economic link between the trade mark owner, Gugler GmbH, and Gugler France, which precluded any likelihood of confusion.

Language and Trade Marks

For an interesting discussion on the extent to which English terms are widely known in the EU, in which a mark including the word TasteSense was found to be confusingly similar to a trade mark for MultiSense for food additives, see the General Court’s judgment in Cases T-108/19 and T-109/19.

Simon Clark

Author