‘Tuna bonds’ in Mozambique – Important arbitration decision from the Supreme Court on the proper approach to s.9 of the Arbitration Act 1996

21.09.2023

On 20 September 2023, the Supreme Court handed down a key decision for all arbitration practitioners on the proper approach to applications under s.9 Arbitration Act 1996. Section 9 allows defendants to legal proceedings brought in breach of an arbitration agreement to apply to the court to stay those proceedings. Section 9 is therefore a key mechanism in England and Wales to enforce arbitration agreements.

Speedread

The Mozambique decision will be essential reading for anyone considering – or facing – an application under s.9 of the 1996 Act. These are the five key points of principle that emerge from the judgment:

- A stay application under s.9 involves a two-stage enquiry. The court must first determine what the ‘matters’ are that the parties have raised or foreseeably will raise in the court proceedings. Second, the court must determine in relation to each such matter whether it falls within the scope of the arbitration agreement, construed appropriately.

- The ‘matter’ need not encompass the whole of the dispute between the parties and partial stays may be granted.

- A ‘matter’ is a substantial issue that is legally relevant to a claim or defence, or foreseeable defence, in the legal proceedings. If the ‘matter’ is not an essential element of the claim or of a relevant defence to that claim, it is not a matter in respect of which the legal proceedings are brought. In short – is the matter on the critical path to establishing a claim or defending against it?

- Identifying the ‘matter’ is a question of judgment and involves applying common sense. The Court will not be swayed by a mechanistic analysis of the pleadings.

- When assessing whether the matter falls within the scope of the arbitration agreement on its true construction, the court must have regard not only to the true nature of the matter but also to the context in which the matter arises in the legal proceedings.

As a bonus, the Court also held on the particular facts of the case that the parties did not agree to stay just the quantum stage of the litigation under s.9 and to send that off to arbitration in circumstances where the liability aspects of the case were not susceptible to such a stay. I would suggest that, except in the rarest of situations, that will be a point of wider application and the English court will not be prepared to bifurcate quantum from liability in response to a s.9 application. To put it another way, the English court will not be prepared to retain jurisdiction over the liability side of a case but to send quantum alone off to arbitration.

The facts

The facts are quite involved and what follows is a basic summary. Between 2013 and 2014, three corporate vehicles wholly owned by the Republic of Mozambique (the ‘SPVs’) entered into supply contracts with three of the respondents (‘Privinvest’) to develop Mozambique’s exclusive economic zone – primarily through tuna fishing and exploiting its gas resources. The contracts were governed by Swiss law. They each contained an arbitration agreement.

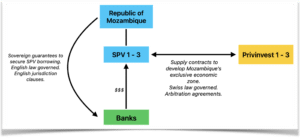

The SPVs borrowed money to fund the work from various banks and Mozambique granted sovereign guarantees to secure that borrowing (the ‘Guarantees’). The Guarantees were governed by English law and provided for dispute resolution in the courts of England and Wales. The set-up looked something like this:

Mozambique now accuses the Privinvest companies and others of paying bribes to Mozambique’s officials, exposing it to a potential liability of approximately US$2bn under the Guarantees. In 2019, Mozambique brought claims in the English courts seeking damages as a result of it entering into the Guarantees. It advanced claims for bribery, conspiracy to injure by unlawful means, dishonest assistance, knowing receipt and a proprietary claim based on sums received by the defendants as a result of the foregoing.

The key legal issue

Section 9 of the 1996 Act provides as follows:

‘(1) A party to an arbitration agreement against whom legal

proceedings are brought (whether by way of claim or

counterclaim) in respect of a matter which under the

agreement is to be referred to arbitration may (upon notice to

the other parties to the proceedings) apply to the court in

which the proceedings have been brought to stay the

proceedings so far as they concern that matter.

…

(4) On an application under this section the court shall grant a

stay unless satisfied that the arbitration agreement is null and

void, inoperative, or incapable of being performed.’

Did Mozambique’s claims before the English court fall within the arbitration agreements in the supply contracts? Should they therefore be stayed under s.9 of the 1996 Act and sent to arbitration instead?

Decision

Section 9 of the 1996 Act gives effect to article II(3) of the New York Convention. The Court therefore considered it appropriate to look at how other countries approach their own equivalents to s.9 and to adopt broad and generally accepted principles when interpreting the 1996 Act. The judgment therefore contains a thorough survey of the international jurisprudence in the area.

Five key points emerge:

- A stay under s.9 involves a two-stage enquiry. The court must first determine what the matters are which the parties have raised or foreseeably will raise in the court proceedings. Second, the court must determine in relation to each such matter whether it falls within the scope of the arbitration agreement, appropriately construed. This involves looking at the claimant’s pleadings but not being overly respectful to the formulations in those pleadings which may be aimed at avoiding a reference to arbitration by artificial means. The exercise involves also looking at the defences, if any, which may be skeletal as the defendant seeks a reference to arbitration, and the court should also take into account all reasonably foreseeable defences to the claim or part of the claim.

- The ‘matter’ need not encompass the whole of the dispute between the parties.

- A ‘matter’ is a substantial issue that is legally relevant to a claim or defence, or foreseeable defence, in the legal proceedings, and is susceptible to be determined by an arbitrator as a discrete dispute. If the ‘matter’ is not an essential element of the claim or of a relevant defence to that claim, it is not a matter in respect of which the legal proceedings are brought. A ‘matter’ is something more than a mere issue or question that might fall for decision in the court proceedings or in the arbitral proceedings and it is not an issue that is peripheral or tangential to the subject matter of the legal proceedings. Is an issue on the critical path to establishing a claim or defending against it?

- Identifying the ‘matter’ is a question of judgment and involves applying common sense. It is not sufficient to identify that an issue is capable of constituting a dispute or difference within the scope of an arbitration agreement without thinking about whether the issue is reasonably substantial and whether it is relevant to the outcome of the legal proceedings.

- When turning to the second stage of the analysis, namely whether the matter falls within the scope of the arbitration agreement on its true construction, the court must have regard not only to the true nature of the matter but also to the context in which the matter arises in the legal proceedings.

On the facts, the Court held that the substance of Mozambique’s claim was that it did not get value for money in entering into the Guarantees. Privinvest asserted in response that it provided valuable goods and services under the supply contracts and that Mozambique had squandered them and sabotaged the project for reasons of internal politics.

The thrust of the Court’s detailed application of the law to the facts of the case from paragraph 81 of the judgment is that Priminvest’s ‘hooks’ into the arbitration agreements in the form of its defences were not relevant answers to Mozambique’s claims on liability. They were therefore not on the critical path to enable them to constitute ‘matters’ in the sense envisaged by s.9 of the 1996 Act. While Priminvest’s arbitration ‘hooks’ might give rise to quantum defences, those defences could only ever arise in the context of proceedings which would themselves not be caught by the arbitration agreements in the supply contracts (see paragraph 106 of the judgment). The question for the court was therefore whether a partial defence on quantum arising in the context of the proceedings, in which the liability claims were not within the scope of the arbitration agreements, was a matter which the parties are to be treated as having agreed to refer to arbitration. The Court held that on the facts, it was not. I would suggest that, except in the rarest of situations, that will be a point of wider application and the English court will not be prepared to bifurcate quantum from liability in response to a s.9 application. In other words, the Court will not be prepared to retain jurisdiction over the liability side of a case but send quantum off to arbitration.

The judgment is available here

Wes Walker

Author