European Court of Justice upholds General Court decision invalidating Red Bull’s blue and silver colour combination marks

30.07.2019

Background

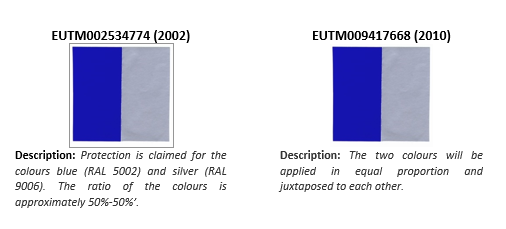

In 2002 and 2010 Red Bull GmbH filed for the following two colour combinations for ‘energy drinks’ within Class 32 of Nice:

Both marks were registered as Red Bull was able to demonstrate acquired distinctiveness through use.

However, the validity of the marks was challenged subsequently on the basis that both marks failed to comply with the requirements of Article 4 and Article 7(1)(a) of Regulation No. 207/2009 (now Art 4 and 7(1)(a) of Regulation No. 2017/1001) as the representation of the marks did not satisfy the Sieckmann criteria, namely that a mark must be clear, precise, self-contained, easily accessible, intelligible, durable and objective.

The Cancellation Division, applying Heidelberger (C‑49/02), held that colour combination marks which constituted the ‘mere juxtaposition of two or more colours, designated in the abstract and without contours’ are insufficiently precise to satisfy Article 4 as such marks allow numerous different combinations of the colours and therefore would not enable a consumer to perceive and recall a particular combination.

On appeal, the decisions of the Cancellation Division were upheld by the First Board of Appeal of the EUIPO on the basis that the marks lacked the precision and durability required by Article 4, such that the combination of colours was not systematically arranged in such a way that the colours concerned are associated in a predetermined and uniform way as required by Heidelberger.

In a further appeal, the General Court (Joined Cases T-101/15 and T-102/15 Red Bull v EUIPO) followed the reasoning of the Board of Appeal, finding that the graphical representations of the Red Bull colour combinations “allowed several different combinations of the two colours” and that the descriptions in each case “did not provide additional precision with regard to the systematic arrangement associating the colours in a predetermined and uniform way”.

Court of Justice (CJEU) decision

Yesterday the CJEU published its decision on the validity of Red Bull’s blue and silver colour combination marks and dismissed the appeal against the General Court’s decision to invalidate the marks.

For present purposes our focus is on the second ground of appeal relating to the infringement of Articles 4 and 7(1)(a) and the applicable principles.

“What you see is what you get”:

Red Bull submitted that the General Court had misinterpreted and misapplied the decision in Heidelberger. According to Red Bull, Heidelberger should be construed narrowly and apply only in circumstances where the description of a colour combination mark permits use of the combination in any conceivable form. By applying Heidelberger in the present case, Red Bull argued that the General Court infringed the “what you see is what you get” rule (Apple C-421/13) which requires that a trade mark is viewed as filed and consequently failed to appreciate the features of the Red Bull marks.

The CJEU rejected this argument noting that, even if the representation in the present case were more precise than in Heidelberger, the requirement for a combination of colours to be arranged systematically by associating the colours concerned in a predetermined and uniform way laid down in that decision applied equally to Red Bull’s marks. The Court confirmed that the General Court was correct to find that the juxtaposition of the two colours side-by-side with an indication as to the ratio of each colour was vague enough to allow arrangement of those colours in numerous combinations and was insufficiently precise to comply with Article 4. The judgement of the CJEU is consistent with the test laid down in Heidelberger as applied by the General Court.

The Court also noted that requiring a colour combination to be systematically arranged by associating the colours in a predetermined and uniform way did not convert the mark into a figurative mark because the test does not mandate the use of contours to define the colour.

According to the CJEU, Red Bull could not rely on the “what you see is what you get” rule in Apple as that was a case concerning “a collection of lines, curves and shapes” not colour combinations and distinguished the case on that basis.

The use of descriptions:

Red Bull also argued that the practical implication of the General Court’s decision was that a mark consisting of a colour combination must include a description with a graphical representation whereas the use of a description has been traditionally at the discretion of the applicant. The CJEU took a light touch on this point on the basis that both marks in question had a description so the argument was ineffective on the facts. The CJEU could have dealt with this point more robustly and taken the opportunity to give clear guidance on the utility of descriptions in colour combination cases. Despite the missed opportunity for the CJEU, given a description was requested by the examiner in respect of the 2010 mark, it seems that descriptions will continue to be a key aspect of colour combination marks and applicants will need to consider carefully the value of a description in colour combination cases.

Actual use of the mark:

As part of this ground of appeal, Red Bull also criticised the General Court for considering the actual use of the mark. Red Bull argued that, as a proprietor of a mark is entitled to use variations of the registered mark (here Red Bull cited Article 15(1) by way of example), marks consisting of colour combinations should not be limited to a single arrangement which reflects actual use of the combination. According to Red Bull, the General Court had erred by considering actual use of the marks. Again the CJEU rejected this argument and confirmed that the General Court was entitled to consider the actual use of the mark as part of its assessment.

Comment:

In light of the Board of Appeal and General Court decisions, the outcome of the CJEU decision is not surprising, but considering the commercial value of the registrations to Red Bull it is equally unsurprising that the case made it all way to the CJEU.

The CJEU decision reaffirms that clarity on the scope of the mark is key to registering a colour combination mark. If the graphical representation and description is not sufficiently precise to define a combination which is systematically arranged by associating the colours in a predetermined and uniform way the mark will not be registerable.

Precisely what that requires from applicants is unclear but, moving forward, it is clear from the Red Bull decision that the mere juxtaposition of colours side by side in a certain ratio will not constitute a valid colour combination mark. Whilst the CJEU has confirmed the test for colour combination marks the Court failed to provide any practical guidance as to how applicants can pass the Heidelberger test.

Even though descriptions are not a mandatory part of the specification, the Red Bull decision illustrates the importance of the description in defining the scope of monopoly in colour combination cases. The difficulty will be for applicants and trade mark attorneys to craft a suitably clear and specific definition that makes the trade mark acceptable without unduly limiting the applicant’s scope of protection.

Applicants should also by mindful that prior use of a colour combination may impact on registerability. Given the nature of colour marks evidence of prior use is typically required to demonstrate acquired distinctiveness. If the nature of the use is inconsistent with the scope of protection sought then the applicant may struggle to register the mark. Therefore, applicants using colour combinations in their branding will need to ensure that graphical representations and descriptions in any future applications are consistent with their historic use of the mark.

Marc Linsner

Author