Aerospace to garden hoses: differing opinions in the English Court of Appeal as to obviousness over obscure prior art

Mishan (T/A Emson) v Hozelock & Ors [2020] EWCA Civ 871

22.07.2020

First published in Kluwer Patent Blog, July 2020.

Since Arnold LJ’s elevation to the Court of Appeal in 2019, he and Floyd LJ have heard about 11 cases together, spanning a mixture of areas of law, some patents cases and some not. In the majority of these cases, Floyd LJ (or a third judge) has given the leading judgment with which Arnold LJ has agreed. In those cases where Arnold LJ gave the leading judgment, Floyd LJ has always agreed. However, this changed on 8 July 2020, when the Court of Appeal handed down its judgment in the above appeal. This time Arnold LJ gave the leading judgment (dismissing the appeal against Nugee J’s judgment from first instance (for which see here)) and Floyd LJ strongly disagreed. Henderson LJ (whose background is in competition law rather than patents) had the unenviable task of deciding between these two highly respected patents judges. Whilst clearly conscious of the expertise of the other two members of the panel, he decided to side with the more junior of the two, Arnold LJ, providing clear reasons for doing so. In a nutshell, as discussed further below, the disagreement was about the approach that should be taken to a piece of prior art which was from a totally different field from that of the claimed invention.

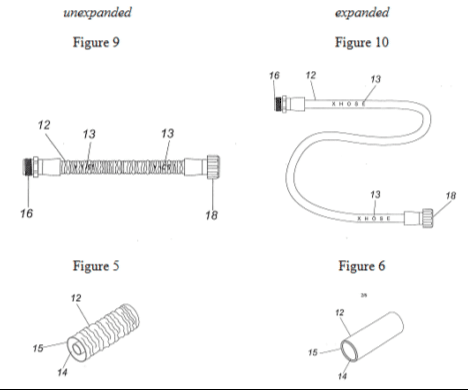

At first instance, Emson (as exclusive licensee of UK Patent 2,490,276 and European Patent (UK) 2,657,585: “the Patents”) had brought infringement proceedings against Hozelock. The Patents protected an extendable hose, such as the “XHose” manufactured by Emson. Emson successfully asserted that Hozelock’s “Superhoze” infringed the Patents; however, Hozelock was successful in its counterclaim to invalidate the Patents which were held to be obvious over a piece of prior art named “McDonald”, which was from the aerospace industry.

The first instance judgment was notable and widely reported, primarily due to the obiter comments about a potentially novelty-destroying prior disclosure by the inventor, Mr Berardi, who had been testing prototypes in his garden in Florida. This interesting aspect of patent law – which on the facts encouraged English patent lawyers to imagine the scenes in Mr Berardi’s garden, with blue skies and presumably a bright green, beautifully watered lawn – had the scope to alter the traditional test for what constitutes a public disclosure. However, this part of the case was only in issue on appeal by way of respondent’s notice, and unfortunately for connoisseurs of patent law, the appeal did not make it to that stage. Rather, the appeal judgment centered on the part of the case which was less likely to conjure up images of Mr Berardi’s Florida garden: the issue of whether Emson’s Patents were obvious over McDonald.

The patents and the skilled person

In short, the patents disclosed a light weight, contractable and kink-resistant garden hose. This hose has an inner and outer tube, where the inner rubber tube expands (lengthways and radially) with incoming water pressure to the width and overall length of the outer nylon tube. The tube then contracts back to its small size on release from the pressurised water.

Notably, this was not the first time that the Patents had been considered by the English Courts. Birss J had held the Patents valid over McDonald in an attack brought by different parties in 2013. However, the attributes of the skilled person were held to be different in that case, based on the differing evidence in the two cases. In the present case, the skilled person had knowledge of technical hoses as well as garden hoses, whereas Birss J’s skilled person was only experienced in garden hoses. Of the four experts who had appeared in the two cases (one on each side for each outing), only one had actual experience in design and manufacture of hoses and therefore knowledge of both technical and garden hoses (a fact described as “remarkable” by Arnold LJ). This was the expert who was favoured by Nugee J at first instance and which therefore led Nugee J to a different conclusion from that of Birss J as to the attributes of the skilled person (and also ultimately the approach to the prior art).

The prior art

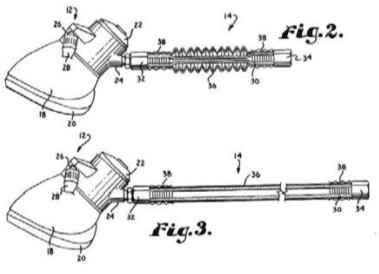

US Patent Application No. 2003/0000530 (“McDonald”) is titled “Self-elongating oxygen hose for stowable aviation crew oxygen mask”.

The abstract of McDonald describes an expanding hose with an inner and outer tube structure. As stated in the specification, the inventive feature is the space saving, self-elongating hose which axially expands when pressurised. A key factor that gave rise to discussion at appeal was that, although McDonald did become a granted patent in some countries, there was no evidence that McDonald was ever implemented or commercialised.

Pozzoli obviousness

In following the established 4-step Pozzoli test for obviousness, Nugee J found that the only difference between the prior art and the Patents was that McDonald was not a garden water hose assembly expanded by water but an aerospace hose expanded by air. Nugee J decided that, standing back, it would have been obvious to the skilled hose designer to take the McDonald hose and adapt it for use as a garden water hose: once presented with McDonald, the skilled person would appreciate how it worked, and the adaptations needed were routine.

On appeal, Emson argued that the judge erred in principle as he conducted a hindsight-based analysis and also failed to take commercial success into account when assessing obviousness.

Appeal judgment

Arnold LJ opened his analysis of whether the judge had erred in relation to hindsight with the statement that, on its face, this appeal seemed unpromising. This was because the judge had made repeated comments about the need to avoid hindsight. Arnold LJ also acknowledged that an aspect of Emson’s argument was slightly more nuanced: that the judge’s reasoning did involve hindsight despite all his attempts to avoid it. Arnold therefore stepped through each of the first instance judge’s findings in relation to McDonald. Two that were particularly relevant were as follows:

- First, that McDonald comes from an entirely separate field (aerospace), and the experts accepted that they would not review patents from this field. Relying on comments from Laddie J in Inhale v Quadrant [2002], Emson submitted that the skilled person would dismiss the document as irrelevant to his work, due to it being from such a distant and unrelated field. This argument was rejected on the basis that, since the skilled person is a designer of hoses in general, even the title of McDonald which includes the words “self-elongating oxygen hose” would lead him to think it might be of interest. Further, relevant elements of the invention in the Patents are placed “up front and exemplified in the embodiments described” in McDonald. Arnold found no error in this approach, stating that the conclusion was one open to Nugee J given that the same hose is frequently used for multiple applications (such as transporting both gases and liquids) and no technical reason was identified as suggesting that McDonald’s hose might be unsuitable for use as a garden hose.

- Another was based on the lack of development in the field of garden hoses: Emson argued that since garden hose design had not changed in many years, the skilled person would be even less likely to make the leap from McDonald. Comparison was made to Dyson v Hoover [2001] where the skilled person’s thinking was “bag-ridden” to the extent they were “blind” to the idea of using a cyclone instead of a bag, or at least prejudiced against it. Here, it was held that a hose designer would immediately have appreciated that McDonald was disclosing a new form of hose, but given there was no comparable evidence of “blindness or prejudice”, Arnold held that it was open to Nugee J to hold that the skilled person would make the necessary leap.

Emson also argued that the skilled person would find McDonald confusing in various different ways, and, for example, that the Judge had cherry-picked the parts of McDonald which support obviousness while ignoring all the inconvenient difficulties with the details, but these arguments were all also dismissed by Arnold LJ.

In the period between the first instance judgment and the appeal, the EPO Opposition Division handed down its decision on one of the Patents, which it found to be inventive over McDonald. Arnold J distinguished this decision on the grounds that the EPO was not faced with precisely the same arguments. Further, the short paragraph in the EPO decision, in his view, did nothing to cast doubt on Nugee J’s detailed reasoning. Indeed, Nugee J’s judgment was excluded from the OD’s assessment.

All of Nugee J’s findings were therefore upheld by Arnold LJ, with whom Henderson LJ agreed. The patent was therefore obvious over McDonald. Nevertheless, both judges were sympathetic to the inventor, Mr Berardi. Henderson LJ went as far as acknowledging that their decision was harsh and potentially even unfair on Berardi. Arnold LJ highlighted, as Nugee J had done, the underlying policy considerations. He accepted that in balancing the monopoly right of the patentee and the public’s right to do something disclosed in the prior art, it is an unfortunate consequence that, as in this instance, clever patents can sometimes be found invalid due to an obscure piece of prior art totally unknown to the inventor.

Dissenting judgment of Floyd LJ

Floyd LJ was clearly more sympathetic to the inventor. He noted the harshness of a situation where an inventor is deprived of his monopoly in order to protect a right in the prior art which would never in fact be exercised. Whilst he acknowledged the policy justification for the rule that any prior art document which the skilled person can access can render a patent obvious, he suggested that the law has found ways of “mitigating against the penal nature of the rule”. Floyd LJ cited Jacob LJ’s comments from Inhale in this respect, that the more distant a prior art document is from the field of the patent, the greater the chance that the skilled person will fail to make the required leap. He indicated that he considered the aerospace field to be so remote, the skilled person would not make that leap. Further, Floyd LJ considered it an “unreality” that the skilled person would seize on an untested proposal from a “very particular and very distant field” when no changes had been made to garden hose design for decades.

Floyd LJ focused heavily on the relatively unknown and non-commercialised McDonald patent application being a “mere paper proposal”, a phrase used by Jacob LJ in the appeal of Grimme v Scott [2010]. Since it had not actually been implemented, he argued that McDonald is simply an untested proposal; a description of an idea. The skilled person would therefore be skeptical as to its use and whether it actually worked, and be even less inclined to adapt it to a different field. He thought it was principally this assumption – that McDonald was a real, practical machine – that infected the first instance judge’s mind with hindsight. In turn, Floyd LJ considered that Nugee J glossed over features of McDonald that the skilled person would otherwise have found confusing (such as precisely how the hose expanded and retracted – Floyd LJ “baulked” at the suggestion that all one is doing in taking McDonald’s idea into the field of garden hoses is transposing an application from one field to another; and he thought that it was “redolent” of hindsight that neither expert could fully understand the detail of how McDonald was supposed to work). He concluded that Nugee J had erred in principle in arriving at his finding of obviousness.

Commercial success

As noted above, the Court of Appeal also considered commercial success. Relying on Laddie J’s judgment in Haberman v Jackel [1999] at [32], Arnold LJ dismissed the arguments quickly on the basis that McDonald was not something that was known to the skilled person. Commercial success could therefore not help to show that the invention was not obvious over McDonald. Floyd LJ and Henderson LJ agreed.

Conclusion

The difference of opinion between Arnold LJ and Floyd LJ shows that hindsight is an ugly subject matter which constantly needs to be grappled with. It is interesting that Arnold J (as he was until last year), was known for his commentary on avoiding hindsight in the instruction of experts (including his criticism of practitioners). Indeed he considered this issue very recently in Fibrogen v Akebia [2020] EWHC 866 (Pat). Yet in this case he has found that there was no error of principle in relation to hindsight.

In this appeal, the majority judgment upholds the application of patent law in relatively strict terms, at the unfortunate expense of a genuinely good idea from an individual in his garden. In future, practitioners might seek to use Floyd LJ’s comments on unknown, “mere paper proposal” ideas (as opposed to real life, worked inventions) as weaker starting points for obviousness attacks, although this may be limited to unusual situations such as this one, where the prior art is from a completely different field.

The case also illustrates how influential the specific expertise of an expert can be in determining the identity of the skilled person, and in turn how the expertise of the skilled person can impact the outcome of a case.

Whatever practitioners think of the outcome, they will be comforted (whilst their clients may be dismayed) to know that even when two highly experienced patent practitioners are faced with exactly the same task and are allowed to review each other’s work, they can come to, and stick with, very different conclusions.

A link to the judgment can be found here.

Brian Cordery

Author

Rachel Mumby

Author

Alex Calver