Impostor! Epic Games releases ‘Among Us’ game mode in Fortnite. What is the legal position?

01.09.2021

Epic Games has introduced a new game mode within its hugely popular game Fortnite, called “Fortnite Impostors”. It involves ten players: eight of which are aiming to maintain the “Bridge” location by completing various “assignments”; and two of which are “impostors” aiming to overtake it. Players must try to work out who the two impostors are and vote them off, while the impostors try to deceive the others and complete their takeover without being voted off by the group. Sound familiar?

If you’re at all interested in the video games industry and haven’t been living under a rock for the past year, you’ll know that the game mode being described is conceptually very similar to last year’s viral hit game, Among Us, which was developed by the small indie games studio Innersloth (they have less than ten employees and had only four when developing Among Us). Innersloth’s developers have taken to Twitter to make clear that Fortnite Impostors is not a collaboration between Innersloth and Epic Games, and to express their disappointment about that. However, has Epic Games actually done anything wrong by implementing the Among Us game concept into Fortnite?

In short, the answer is no. The two key intellectual property rights that might have assisted Innersloth are patents and copyright, but neither are likely to apply to protect the Among Us game mechanics.

Patents

In a tweet last week, one of the Innersloth developers claimed that they “didn’t patent the Among Us mechanics” because that doesn’t “lead to a healthy game[s] industry”. This statement implies that Innersloth could have obtained a patent to prevent Epic Games from releasing its own Imposters game mode had it wished to do so, but that is probably not true. Video game patents are notoriously difficult to obtain, both in the US, where Innersloth would most likely have first filed for a patent, and in the UK and Europe, which is the focus of this article. Why?

Well, computer programs are specifically excluded from patentability by Article 52(2)(c) of the European Patent Convention. Therefore, in order to obtain a patent for any computer program (or video game), a specific further technical effect is required beyond the technical interaction between program (software) and computer (hardware). In other words, a patent will only be granted for inventions which have some additional technical effect that goes beyond the usual, expected result of a computer program operating on a computer (or console). This is challenging when it comes to video games which, by their nature, are simply computer programs running on computers.

A further difficulty for Innersloth is that game rules are expressly excluded from patentability, again by Article 52(2)(c) of the European Patent Convention. Unless, the Innersloth developers meant something more specific than the rules of Among Us when referring to patenting the “Among Us mechanics”, this exclusion would apply.

The “Konami” case (Case T 0928/03) is a good example of a video game patent granted because the invention provided for a further technical effect beyond the interaction between program and computer, and which related to more than the game rules. Konami obtained a patent, relating to its Pro Evolution Soccer football video game, for a method by which players of its games are able to identify both the footballer they are controlling at any given moment, and also the teammates to which the ball can be passed (even if those teammates are off screen) through the use of “guide marks”, and all whilst maintaining a level of zoom that allows a player to focus on the game. The in-game effect of the guide marks and graphic user interface solved the technical problem of players requiring a particular level of zoom on their active player, whilst still being able to understand where their teammates are outside of that zoomed in area. That solution was not merely the effect of program interacting with computer, nor a part of the rules of the game.

Regardless of all the above difficulties with the patentability of video games generally, Innersloth would be likely to fall at an earlier hurdle anyway; that is because the Among Us game concept is not particularly original or inventive, both prerequisites for patent validity. A number of other social deduction games existed prior to Among Us that have a similar format, and all of them are based on popular live party games, particularly “Mafia” (otherwise known as “Werewolf“). While Innersloth has certainly skyrocketed the popularity of this game concept in video games over the past year or so with Among Us, it has not invented something new here that would justify patent protection.

We didn’t patent the Among Us mechanics. I don’t think that leads to a healthy game industry. Is it really that hard to put 10% more effort into putting your own spin on it though?

— Puff (@PuffballsUnited) August 17, 2021

Copyright

Copyright is often the go-to intellectual property right for video game developers seeking to protect their games. However, in this case a claim for copyright infringement by Innersloth would also be unlikely to succeed; this is due to a fundamental rule of copyright well-known as the idea/expression dichotomy. Copyright protects the specific expression of original works, but will not protect the broader ideas behind those works.

In the UK, this issue of copyright protection of video games and their formats has been addressed in the leading Court of Appeal case, Nova Productions Limited v Mazooma Games Limited, relating to arcade-style pool computer games. Nova Productions’ claim for copyright infringement failed because there could be no copyright in the ideas and principles behind the game, such as the movement of the cue and the theme of pool in the game. While there was no doubt about the fact that copyright would protect the game’s artistic works as expressed, i.e. the specific still images of the pool game, there was found to be no infringement because there had not been a substantial reproduction of those artistic works in each frame of Mazooma’s game. So how does this apply to Among Us and Fortnite Impostors?

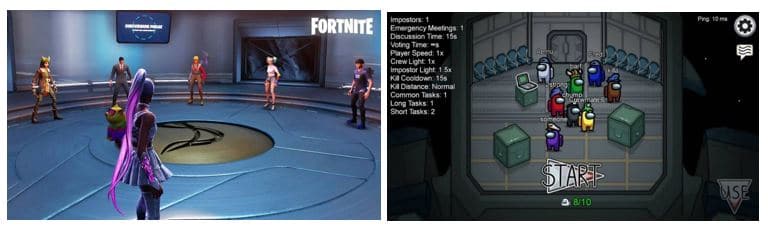

In this case, Innersloth would be seeking to protect the rules, concepts and ideas behind Among Us, not the specific expression of those ideas in their game. That makes sense when you look at the games compared side-by-side as below. Epic Games’ version of the social deduction game mode looks, and probably plays, nothing like Among Us aside from the rules of the game. Fortnite Impostors does use similar terminology to Among Us (in which the antagonists are also called “impostors”) and the “Bridge” location map layout appears somewhat similar to Innersloth’s “Skeld” map design (as highlighted by another Innersloth developer in a tweet here). Yet, the game doesn’t reproduce any of the properly copyright-protected works from Among Us, such as the audio-visual works in the game or the source code underlying it. Fortnite Imposters uses Fortnite’s own art style, a third-person view and 3D map, whereas Among Us uses an indie-style bird’s eye view and 2D map. Therefore, for almost identical reasons to those given in the Nova Productions judgment, any claim by Innersloth against Epic Games based in copyright would likely fail.

Conclusion

Legally, there is nothing wrong with Epic Games’ Fortnite Impostors game mode, and there isn’t much that Innersloth can do about it (except for complaining on Twitter) and perhaps rightly so. There is a reason game rules, genres and concepts are so difficult to protect – as Lord Justice Jacob stated in the Nova Productions case:

“If protection for such general ideas as are relied on here were conferred by the law, copyright would become an instrument of oppression rather than the incentive for creation which it is intended to be. Protection would have moved to cover works merely inspired by others, to ideas themselves”.

Indeed, Epic Games’ “Fortnite Battle Royale” game mode was heavily inspired by other games that started the craze (including PlayerUnknown’s BattleGrounds, whose creators brought a claim against Epic back in 2018 but quickly dropped it, possibly for the reasons described in this article), and those games were developed based on other media, such as Japanese movie Battle Royale from 2000 and even The Hunger Games’ series of books and films.

When compared in that light, it becomes clear why the legal position is as it is – media creations, including books, films, art and even games are often iterative; so long as the specific expression of the media hasn’t been reproduced, artists and developers should have the freedom to compete and develop upon one another’s ideas.

Charles Purdie

Author