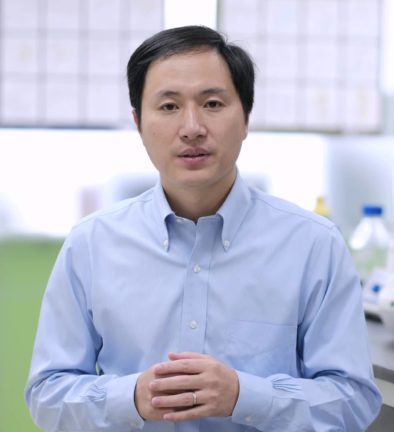

Beware of cheap imitations: justice and He Jiankui

17.01.2020

Following our public survey on genome editing last summer (published here) and our related debate back in November, BioNews asked Julian Hitchcock to write an opinion piece on the conviction of He Jiankui (JK), the rogue human genome editor. The article was first published in BioNews, on 13 January 2020. You can read it below, and you can see sources and references at: https://www.bionews.org.uk/page_147171.

‘Three babies, three scientists, three years in jail, and a three million yuan fine. This is the story of Dr He Jiankui (JK) and the world’s first genome-edited babies’, wrote the philosopher Françoise Baylis in last week’s Boston Globe.

The legal story looks trite: laws were broken, and punishment ensued. Had the scientists done the same deeds in the UK, very similar consequences would have followed. Applause for China, however, must be one-handed.

The worst aspect of the case is its lack of transparency. Instead of a published judgment and legal explanation for JK’s prior detention, about which Chinese authorities have been both opaque and touchy, a somewhat ambiguous press release emerged stating that the hearing was held in private ‘due to the personal privacy of the persons involved’, mushing the report with a paragraph emphasising the government’s other responses to the JK scandal.

Having investigated the genome editing baby incident expeditiously, Guangdong’s provincial government had taken serious measures and held units and personnel accountable ‘in accordance with relevant regulations’. Moreover, those involved had been blacklisted from engaging in assisted reproductive technology (ART) by the National Health Commission, prohibited from applying for public research funds by the Ministry of Science and Technology, and banned from using human genetic resources, in each case for life.

Such judicial/governmental sanctions make JK’s initial confidence appear startling. He and his associates were hardly oblivious of the fact that China’s 2003 ART Regulation expressly prohibits ‘the use of genetically manipulated human gametes, zygotes and embryos for the purpose of reproduction’ in a part usefully entitled ‘Technical Norms in Human ART’, which they would know to comprise licence conditions for IVF clinics and ART centres. They would also know that a part of the ART Regulation dubbed ‘Ethics Guiding Principles of ART & Sperm Banks’ placed the welfare of offspring and prevention of commercialisation among its paramount concerns. Nor would they be oblivious to the fact that the ministry responsible for IVF/ART licences, the National Health and Family Planning Commission (NHFPC), can shut down institutions offering unauthorised or illegal services.

Nevertheless, when it came to flout these regulations the Xinhua press report tells us that He and his colleagues really pushed the boat out. They conspired to obtain commercial benefit from untested genome editing technology, forged ethical review materials, recruited scientists to undertake editing and ART work for multiple HIV-infected couples without telling them the true nature of the work, and secured two pregnancies and three genome-edited babies.

It’s remarkable, therefore, that the scientists took government funding for a project falling within China’s ’13th Five Year Plan (2016-2020)’, and proudly announced their accomplishments at an international conference. Why would they take the risk?

Notably, the defendants’ criminal liability did not directly apply to the implantation of genome-edited embryos. Although the court noted that they had ‘crossed the scientific and medical ethics bottom line’, none of the various violations of administrative regulations and ethical norms were illegal under China’s civil or criminal laws. Their actions had, however, ‘disrupted medical treatment’. The court seems to have decided that, as the licensed practitioners who executed the forbidden steps at the group’s orders were unaware of the illegality, the three were themselves undertaking a medical activity. As none had a licence to do so, they were guilty of illegal medical practice’. The deliberate breach of regulations could be reflected in sentencing, but the criminal liability had to be devised.

This is significant, because the authorities have not only ignored the ART Regulation’s widely-flouted prohibition of surrogacy arrangements, as mediated by licensed medical practitioners, but even taken steps to remove it. Could this explain JK’s extreme self-confidence? If surrogacy, why not human germline genome editing? Why shouldn’t the ‘Technical Norms’ that He and his colleagues so confidently and publicly breached also be ignored and rewritten? After all, as ministerial guidelines, the ‘Technical Norms’ could be more readily amended than primary laws, and NHFPC itself is responsible for drafting them.

The primary law is evolving: China is reforming its Civil Code to specify preconditions for hereditable genome editing, with a meeting of bioethicists and scholars scheduled for 12 January, when they may perhaps consider criminalising breach. Simultaneously, draft regulations on the clinical application of new biomedical technologies require ‘changes in genetic material or… expression’, including genome editing, to be managed by the State Council health authority, not provincially.

It looks positive, but China’s criminal justice system and human rights records hardly inspire trust. The contrast between JK’s initial confidence and subsequent punishment, and China’s dubious motive for concealing the legal basis of his detention and judgment, suggest an institutional involvement that tarnishes China’s status as a science superpower, which needs far greater transparency and due process.

—

You can watch a full video of the Bristows’ Life Sciences Debate 2019 – The quest for the perfect human..? here.

Julian Hitchcock